Problem definition

Together with every build, we need to generate a document that lists all the important classes and their methods, and how these classes are connected with each other. This may seem like a toy problem, but it gives us enough context to learn what tools to look for and what to expect from them.

Solution

In our solution, there are going to be 2 modules:

docs— implementation of all the analysis tools.sample-app— the target application that we want to document.

It’s important to introduce this separation, because docs is a library that only needs to be built once and then can be reused in different applications. sample-app is a toy application we’re going to document.

Document production process

Asciidoctor is a great choice when you want to produce a nice-looking document (in my {% post_link Use-Asciidoctor-to-create-great-publications other post %} I’ve explained why). Asciidoctor is easy to integrate with Gradle using the asciidoctor-gradle-plugin which means that we can just put our documentation sources together with Java sources and run ./gradlew asciidoctor to produce the documentation.

It would be that easy if our documentation had to be entirely written by a human, but in our case we want to generate pieces of document from code, so we’ll have a document like this:

= Sample App docs

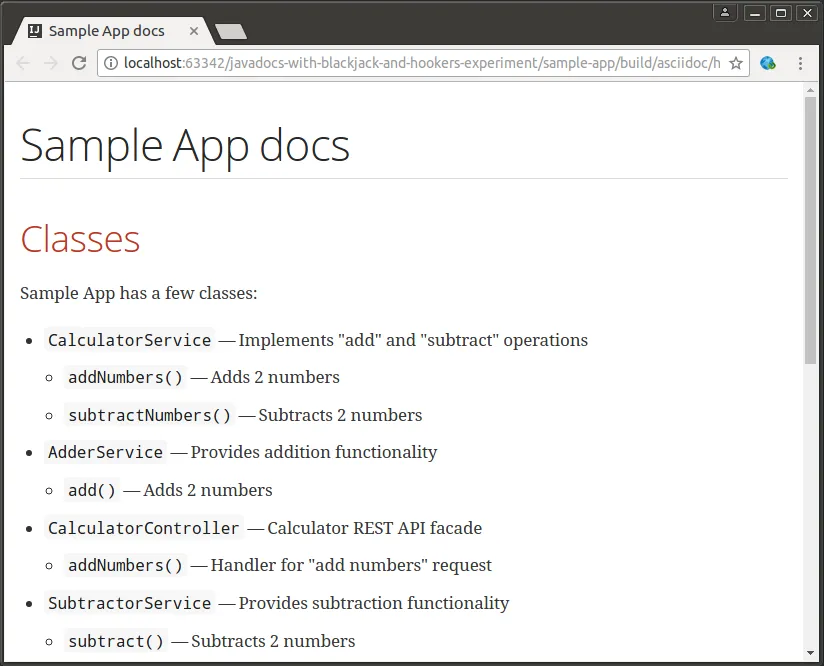

== Classes

Sample App has a few classes:

include::{snippetsDir}/classes.adoc[]

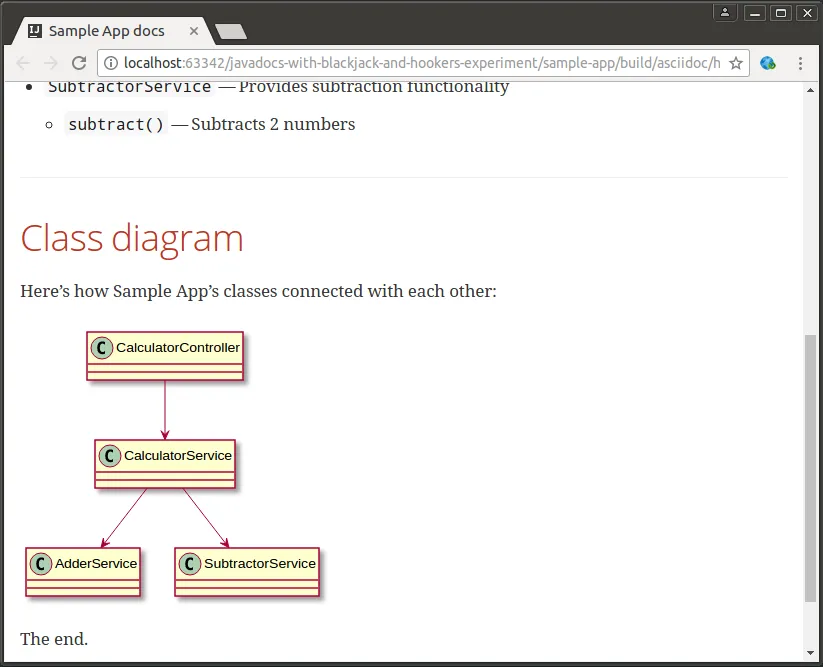

== Class diagram

Here's how Sample App's classes connected with each other:

include::{snippetsDir}/class-diagram.adoc[]

The end.classes.adoc and class-diagram.adoc are the snippets which we’ll generate during the test run. We make Gradle’s asciidoctor task depend on test task — this guarantees that test run artifacts will be there by the moment Asciidoctor starts working. So, the build scenario looks like this:

- Step one: run JUnit tests and produce the

classes.adocandclass-diagram.adocsnippets. - Step two: run Asciidoctor and let it use content from previously generated

classes.adocandclass-diagram.adocsnippets to render the “main” document —docs.adoc.

Producing the snippets

Here’s what our JUnit tests should look like:

public class DocTest {

private final SnippetGenerator snippetGenerator =

new SnippetGenerator(new File(System.getProperty("sourceDir")));

private final SnippetWriter snippetWriter =

new SnippetWriter(Paths.get(System.getProperty("snippetsDir")));

@Test

public void documentClasses() {

String snippet = snippetGenerator.generateClassesSnippet();

snippetWriter.writeSnippet("classes.adoc", snippet);

}

@Test

public void documentClassDiagram() {

String snippet = snippetGenerator.generateClassDiagramSnippet();

snippetWriter.writeSnippet("class-diagram.adoc", snippet);

}

}SnippetGenerator is a service that reads the code and produces the snippet content. Its constructor has a single parameter — path to source code directory.

SnippetWriter is a service that takes the content and writes it to the file. Its constructor has a single parameter — path to the directory where to write snippet files.

By making these paths configurable, we achieve nice integration with Gradle:

ext {

sourceDir = file('src/main')

snippetsDir = file('build/generated-snippets')

}

test {

systemProperty 'sourceDir', sourceDir

systemProperty 'snippetsDir', snippetsDir

}How SnippetGenerator works

The big idea behind SnippetGenerator consists of these 2 parts:

- Use QDox to read the code. QDox makes it easy to get all the codebase details we need: classes, methods, Javadoc comments, everything. If you’re not familiar with QDox, take a look at {% post_link Enforce-software-design-with-Checkstyle-and-QDox my other post %} where I show how to analyze Java code using QDox.

- Use EJS and Nashorn to generate snippet contents based on QDox models. EJS is a good choice here, because it allows you to mix templates with raw JavaScript. Nashorn’s runtime environment allows JavaScript to work with Java objects.

Let me illustrate it with pseudocode. Here’s a dummy EJS template:

We have <%= qdox.getClasses().size() %> classes!And here’s the code to render this template:

QDox qdox = new QDox("src/main/java");

nashorn.put("template", readAsText("dummy.ejs"));

nashorn.put("qdoxObject", qdox);

String snippet = nashorn.eval("ejs.render(template, {qdox: qdoxObject})");Assuming that we had 10 classes in our src/main/java, the snippet will have a value of:

We have 10 classes!How SnippetGenerator actually runs EJS with Nashorn

While the pseudocode above explains what happens, let’s take a closer look at how to actually run EJS on Nashorn. First, EJS needs a global window object to initialize properly. Second, it’s important to make a proxy object for original model object. Here’s the “minimal” EJS runner that does all the heavy lifting:

private static String renderEjs(String templateString, Object model) {

ScriptEngineManager scriptEngineManager = new ScriptEngineManager();

ScriptEngine engine = scriptEngineManager.getEngineByName("nashorn");

engine.put("template", templateString);

engine.put("model", model);

engine.eval("var modelProxy = Object.bindProperties({}, model)");

engine.eval("window = {}");

engine.eval("load('classpath:" +

"META-INF/resources/webjars/ejs/2.4.1/ejs-v2.4.1/ejs.js')");

return (String)engine.eval("window.ejs.render(template, modelProxy)");

}Our only use-case assumes that model is always the same — a JavaProjectBuilder object, so here is the convenient render() method that loads the template by name and passes the JavaProjectBuilder object to it:

private File sourceRoot;

...

private String render(String templateResourcePath) {

String templateString = getResourceAsString(templateResourcePath);

JavaProjectBuilder javaProjectBuilder = new JavaProjectBuilder();

javaProjectBuilder.addSourceTree(sourceRoot);

return renderEjs(templateString, javaProjectBuilder);

}This allows us to provide these 2 convenience methods to the end user:

public String generateClassesSnippet() {

return render("classes.ejs");

}

public String generateClassDiagramSnippet() {

return render("class-diagram.ejs");

}Generating the “list of classes” snippet

Here’s how the template for “list of classes” looks like:

<% load('classpath:utils.js');

var classes = getClasses();

for each (var clazz in classes) {

if(shouldSkip(clazz)) continue; %>

* `<%= clazz.getName() %>` -- <%= clazz.getComment() %>

<% for each (var method in clazz.getMethods()) { %>

** `<%= method.getName() %>()` -- <%= method.getComment() %>

<% } %>

<% } %>Because our model is JavaProjectBuilder object itself, we call getClasses() as if it was a global function. In real world I would consider moving the querying away from templates — I would build more template-specific models in Java and then just let EJS do the final formatting. I don’t follow this approach in this post to keep it as short and clear as possible.

The shouldSkip() function comes from utils.js. It checks if class is annotated with Javadoc @undocumented tag, and if so, it returns true:

function shouldSkip(clazz) {

return clazz.getTagByName('undocumented') != null;

}When we render the classes.ejs template, the result is Asciidoctor markup of a 2-level unordered list:

* `CalculatorService` -- Implements "add" and "subtract" operations

** `addNumbers()` -- Adds 2 numbers

** `subtractNumbers()` -- Subtracts 2 numbers

* `AdderService` -- Provides addition functionality

** `add()` -- Adds 2 numbers

* `CalculatorController` -- Calculator REST API facade

** `addNumbers()` -- Handler for "add numbers" request

* `SubtractorService` -- Provides subtraction functionality

** `subtract()` -- Subtracts 2 numbersWhen it gets included into main document and rendered, the final picture looks like this:

Generating the “class diagram” snippet

We do a very similar thing to make a class diagram. This time we’re using Asciidoctor’s diagramming support and namely PlantUML syntax for class diagrams:

[plantuml, class-diagram, svg]

----

<% load('classpath:utils.js');

var classes = getClasses();

for each (var clazz in classes) {

if(shouldSkip(clazz)) continue; %>

class <%= clazz.getName() %>

<% } %>

<%

for each (var clazz in classes) {

if(shouldSkip(clazz)) continue;

for each (var field in clazz.getFields()) {

if(shouldSkip(field.getType())) continue; %>

<%= clazz.getName() %> --> <%= field.getType().getName() %>

<% }

} %>

----This template generates a result like this:

[plantuml, class-diagram, svg]

----

class CalculatorService

class AdderService

class CalculatorController

class SubtractorService

CalculatorService --> AdderService

CalculatorService --> SubtractorService

CalculatorController --> CalculatorService

----Which becomes a nice class diagram when finally rendered:

Conclusion

Building custom documentation is not the most popular task, but when it appears, make sure to come up with a reproducible solution. EJS, Asciidoctor and Gradle make it surprisingly easy to produce pieces of the document during the build. While in this post we were using QDox as a source of data, the approach won’t change significantly if instead of Java code you’ll need to analyze anything else.

See a self-sufficient sample project in this GitHub repository.

Andrey Agibalov

Andrey Agibalov