Javadoc comments are a nice approach to documenting the code. By following a specific comment structure, you can describe what the classes are responsible for and what the methods do. Many developers use the standard javadoc tool to generate documentation.

But what if your client asks for custom documentation? In this post I want to show how QDox and Asciidoctor make it a straightforward task.

Problem definition

Together with every build, we need to generate a document that lists all the important classes and their methods, and how these classes are connected with each other. This may seem like a toy problem, but it gives us enough context to learn what tools to look for and what to expect from them.

Solution

In our solution, there are going to be 2 modules:

docs– implementation of all the analysis tools.sample-app– the target application that we want to document.

It’s important to introduce this separation, because docs is a library that only needs to be built once and then can be reused in different applications. sample-app is a toy application we’re going to document.

Document production process

Asciidoctor is a great choice when you want to produce a nice-looking document (in my other post I’ve explained why). Asciidoctor is easy to integrate with Gradle using the asciidoctor-gradle-plugin which means that we can just put our documentation sources together with Java sources and run ./gradlew asciidoctor to produce the documentation.

It would be that easy if our documentation had to be entirely written by a human, but in our case we want to generate pieces of document from code, so we’ll have a document like this:

1 | = Sample App docs |

classes.adoc and class-diagram.adoc are the snippets which we’ll generate during the test run. We make Gradle’s asciidoctor task depend on test task – this guarantees that test run artifacts will be there by the moment Asciidoctor starts working. So, the build scenario looks like this:

- Step one: run JUnit tests and produce the

classes.adocandclass-diagram.adocsnippets. - Step two: run Asciidoctor and let it use content from previously generated

classes.adocandclass-diagram.adocsnippets to render the “main” document –docs.adoc.

Producing the snippets

Here’s what our JUnit tests should look like:

1 | public class DocTest { |

SnippetGenerator is a service that reads the code and produces the snippet content. Its constructor has a single parameter – path to source code directory.

SnippetWriter is a service that takes the content and writes it to the file. Its constructor has a single parameter – path to the directory where to write snippet files.

By making these paths configurable, we achieve nice integration with Gradle:

1 | ext { |

How SnippetGenerator works

The big idea behind SnippetGenerator consists of these 2 parts:

- Use QDox to read the code. QDox makes it easy to get all the codebase details we need: classes, methods, Javadoc comments, everything. If you’re not familiar with QDox, take a look at my other post where I show how to analyze Java code using QDox.

- Use EJS and Nashorn to generate snippet contents based on QDox models. EJS is a good choice here, because it allows you to mix templates with raw JavaScript. Nashorn’s runtime environment allows JavaScript to work with Java objects.

Let me illustrate it with pseudocode. Here’s a dummy EJS template:

1 | We have <%= qdox.getClasses().size() %> classes! |

And here’s the code to render this template:

1 | QDox qdox = new QDox("src/main/java"); |

Assuming that we had 10 classes in our src/main/java, the snippet will have a value of:

1 | We have 10 classes! |

How SnippetGenerator actually runs EJS with Nashorn

While the pseudocode above explains what happens, let’s take a closer look at how to actually run EJS on Nashorn. First, EJS needs a global window object to initialize properly. Second, it’s important to make a proxy object for original model object. Here’s the “minimal” EJS runner that does all the heavy lifting:

1 | private static String renderEjs(String templateString, Object model) { |

Our only use-case assumes that model is always the same – a JavaProjectBuilder object, so here is the convenient render() method that loads the template by name and passes the JavaProjectBuilder object to it:

1 | private File sourceRoot; |

This allows us to provide these 2 convenience methods to the end user:

1 | public String generateClassesSnippet() { |

Generating the “list of classes” snippet

Here’s how the template for “list of classes” looks like:

1 | <% load('classpath:utils.js'); |

Because our model is JavaProjectBuilder object itself, we call getClasses() as if it was a global function. In real world I would consider moving the querying away from templates – I would build more template-specific models in Java and then just let EJS do the final formatting. I don’t follow this approach in this post to keep it as short and clear as possible.

The shouldSkip() function comes from utils.js. It checks if class is annotated with Javadoc @undocumented tag, and if so, it returns true:

1 | function shouldSkip(clazz) { |

When we render the classes.ejs template, the result is Asciidoctor markup of a 2-level unordered list:

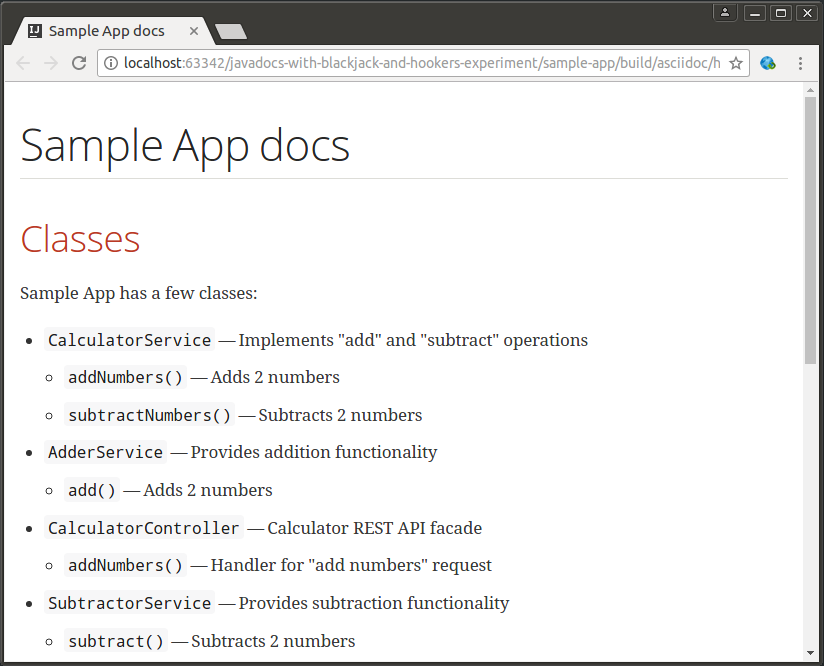

1 | * `CalculatorService` -- Implements "add" and "subtract" operations |

When it gets included into main document and rendered, the final picture looks like this:

Generating the “class diagram” snippet

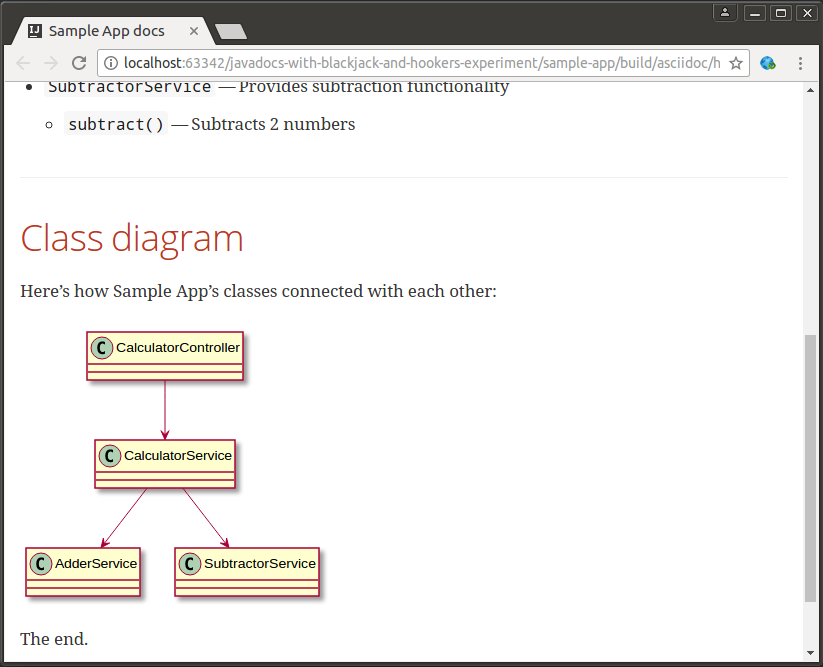

We do a very similar thing to make a class diagram. This time we’re using Asciidoctor’s diagramming support and namely PlantUML syntax for class diagrams:

1 | [plantuml, class-diagram, svg] |

This template generates a result like this:

1 | [plantuml, class-diagram, svg] |

Which becomes a nice class diagram when finally rendered:

Conclusion

Building custom documentation is not the most popular task, but when it appears, make sure to come up with a reproducible solution. EJS, Asciidoctor and Gradle make it surprisingly easy to produce pieces of the document during the build. While in this post we were using QDox as a source of data, the approach won’t change significantly if instead of Java code you’ll need to analyze anything else.

See a self-sufficient sample project in this GitHub repository.